For Clinicians

The Therapies

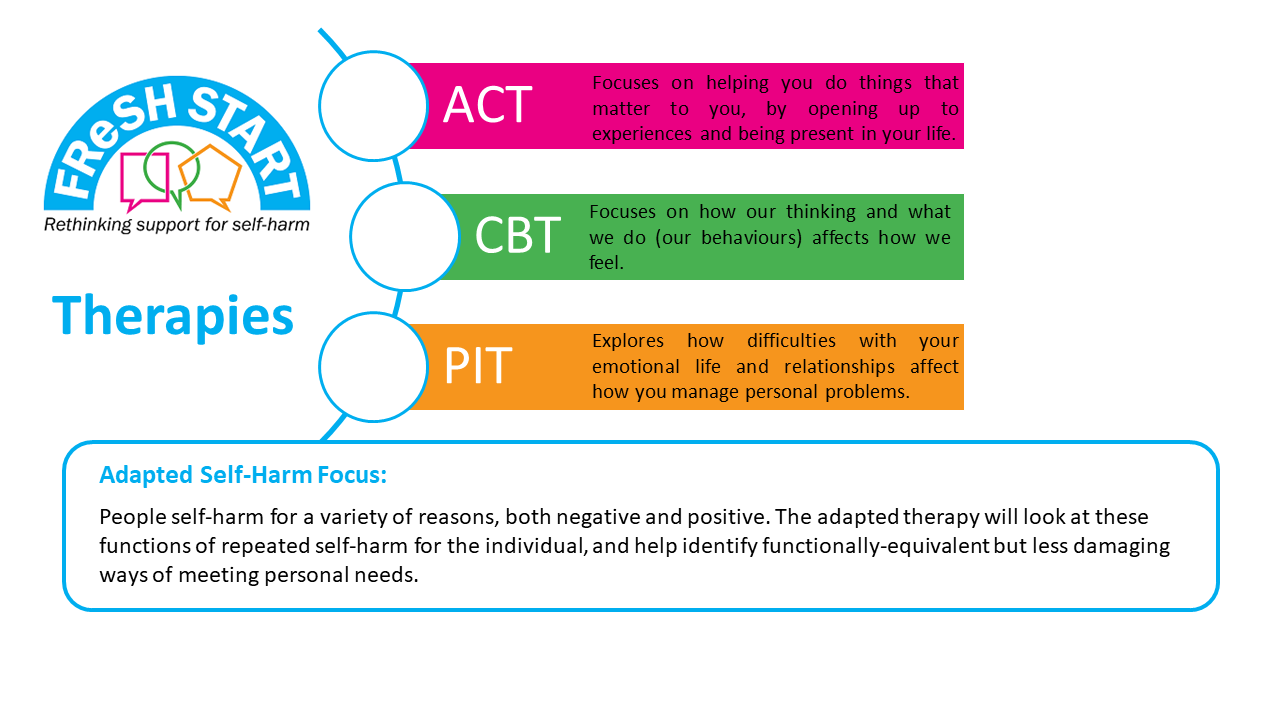

The three therapies which have been chosen for FReSH START are behavioural/cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Psychodynamic-Interpersonal Therapy (PIT). These therapies are all different in their approach but can be easily adapted to incorporate findings from the first parts of the FReSH START programme and prior research, which suggests that understanding the function(s) that self-harm performs for an individual is important, particularly the recognition that self-harm may perform a positive function, such as blocking difficult feelings or providing some sense of calm.

In all three therapies, a similar assessment process will be undertaken, which involves helping the client to understand the purpose (s) of their self-harm. This includes understanding clients’ needs and values, their relationships with others, and the way they deal and manage difficult feelings or stress, including their habitual thought processes, their flexibility of thinking and the way they manage problems. Each of the therapies may particularly focus upon certain areas according to the approach they use, so for example, BT/CBT may focus more on clients’ thought processes, PIT on their interpersonal processes and ACT on their flexibility of thinking.

The therapies have been modified so they can be taught relatively quickly with NHS mental health staff who are familiar with managing risk and have experience of seeing clients’ who self-harm but have no particular prior training in psychotherapy. We intend to train mental health staff to deliver the therapies by offering intensive brief training followed by ongoing supervision. This model of training has been used in the NHS in self-harm services to train staff and reflects two key considerations:

a) there is a high turnover of staff in acute mental health services-so brief training followed by ongoing supervision is an efficient model

b) recognised therapists who have undergone a lengthy training programme in talking therapies, struggle to manage risk, unless they have had prior experience of working in acute settings.

All three therapies will consist of 12 weekly 50 minute sessions of one to one therapy with a nurse therapist/mental health professional therapist. There is the possibility of two further telephone sessions if this is deemed necessary by the client and therapist. All the therapists will receive on–going supervision in groups of 2-3 on a regular basis. All three therapies will incorporate risk assessment and safety planning into their approaches and the therapists will be closely aligned with acute mental health services, in most cases, liaison mental health teams.

More Information on Each Therapy

BT/CBT

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) is a brief talking therapy that is commonly used to help people with problems such as anxiety and depression, but can be helpful in other situations too.

It is based on the cognitive behavioural model, which states that:

- For every situation in life we can break this down into the components of thoughts, feelings, behaviours and physiology, each of which can affect the other.

- A cognitive approach emphasises that how we think about situations affects how we feel, rather than being a direct result of the situation. In addition, how we respond (our behaviours) can reinforce our initial thoughts and stop us finding out whether our initial thoughts are helpful.

- This can then set up vicious circles that keep the problem going.

- Early experiences and previous life experiences are seen as shaping the way we think about things, including ourselves, other people, the future and so on. This can often lead to us developing strategies to cope with these beliefs. These strategies are helpful initially and often help us survive difficult childhoods, but can cause us problems if we stick too rigidly to them in adulthood.

The therapy initially helps us define problems that we want to work on, and set goals, and then it helps us identify the vicious circles that keep these problems going, in particular the patterns of thinking and behaviour that maintain these difficulties.

Once we have established these patterns, the aim of therapy is to help break these cycles by looking at our thinking patterns or our behaviour patterns. For example thinking or cognitive interventions aim to either help us first identify our thoughts about a particular situation. We can then either learn to think differently or perhaps test out the accuracy of these thoughts through experiments, change how we think about a situation, or else help us learn to take a step back from our thoughts.

The behavioural part of CBT sees a close link between what we do and how we feel. Its goal, therefore, is to help us change what we do in order to change our feelings. It is particularly interested in understanding why a behaviour occurs. It looks closely at what the triggers for the behaviour are and what happens afterwards, in terms of thoughts, feelings and behaviours that may keep the behaviour going.

We keep doing behaviours because of what happens. If a behaviour works or helps us in some way, we keep doing it. If it doesn’t, we stop doing it. Timing matters when trying to understand what helps or works. What helps in the moment or the short-term may not be so helpful in the long run. If it works in the short-term, though, we’ll tend to keep doing it, even if it is less helpful in the long-term.

Behavioural interventions involve trying out new behaviours that may help the person feel better in both the short-term and long-term.

Typical CBT is:

- Structured: we set an agenda at the beginning of each session

- Collaborative: we acknowledge the patient is the expert in their difficulties while we have the knowledge of the therapy, but we want to contribute equally

- Uses lots of summaries and two-way feedback

- Uses a type of questioning style called Socratic questioning

- Helps patients identify problems and goals

- Uses an individualised understanding of the patient’s difficulties to guide the treatment

- Identifies thoughts feelings behaviours and physiology

- Uses between-session tasks

- Uses behavioural experiments

- Evidence based.

Why BT/CBT for NHS services managing repeated self-harm

CBT approaches to self-harm seek to understand the functions of the behaviour drawing broadly on operant conditioning principles while also recognising that the behaviour is triggered by cognitions that serve to facilitate the behaviour. These cognitions may relate to fundamental beliefs about the self (e.g., ‘I am worthless and deserve punishment’), beliefs that facilitate the behaviour (‘There is no other way to deal with how I feel at the moment’) and beliefs about the consequences of the behaviour (e.g., ‘This proves I am worthless’, ‘This proves there is no other way to cope’).

Treatment consists of identify the various functions of the self-harm behaviour and the supporting cognitions. Interventions involve identifying alternative behaviours that may serve the same function, evaluating the supporting cognitions and conducting behavioural experiments to test out those cognitions.

ACT

Acceptance-based behaviour therapy has developed over the past 20 years. ACT does not explicitly aim to reduce distress or to change the content negative thoughts. Instead, ACT aims to enable effective action in the presence of competing sources of psychological influence (this might include emotions and thoughts, sensations, habits), helping a person to align their behaviours with their overarching values. The treatment components of ACT can be distilled into a process called psychological flexibility, which can be defined as consisting of three components: the capacity to persist or to change behaviour in a way that 1) includes conscious and open contact with thoughts and feelings (openness), 2) appreciates what the situation affords (awareness), and 3) serves one’s goals and values (engagement)”.

ACT uses a range of methods to engender psychological flexibility. In its most basic form, the therapist will explore the participant’s ‘values’: freely chosen qualities of ongoing action that serve as intrinsically reinforcing means to co-ordinate future behaviour. (Examples might be performing as a nurturing parent, or creativity in work.) Participants are encouraged consciously to initiate actions that support these values: e.g. spending time with children, disclosing emotions and opinions, etc. To assist this committed action, the therapist facilitates development of the openness and awareness aspects of psychological flexibility. This entails the teaching of various aspects of mindfulness practice, defusion (learning to notice the actions of the mind as separate from the self), perspective-taking and self-compassion exercises.

Why ACT for NHS services managing repeat self-harm

Unlike treatments used most regularly in the context of self-harm, the focus of ACT is not on learning to control painful emotions. It instead teaches participants to take a broader perspective on their behaviours (including self-harm); to notice whether behaviours are taking them closer to, or further away from their own personal values in the longer-term; and in so doing to open-up to emotions and step-back from thoughts that interfere with meaningful activity.

ACT can help where positive, and not just negative, factors help to maintain self-harm behaviour. For example, mastery functions of self-harm may include positive reinforcement via consequential pleasurable self-conceptualisations/thoughts (success, in control), emotions (pleasure, vitality, confidence, relaxation etc.) or responses from others/systems. To intervene in this process, ACT participants explore their values with the clinician, to get a sense of what is personally meaningful to them (e.g. being present to their children, supporting others, etc.). From here they are taught ways to notice whether self-harm behaviours are – from a broader perspective – interfering with, or helping them to make progress on, their values. The goal is to encourage the participant to develop a habit of associating decisions to forgo self-harm with their own over-arching values (e.g. being a present parent, a creative worker). The influence of competing sources of psychological influence (here reinforcing positive feelings, thoughts, behaviours) can also be reduced in several ways: The therapist will help the participant learn to notice, distance from, and open-up to, positive thoughts and feelings that come with self-harm. It could be that learning to distance from thoughts regarding mastery, as opposed to getting entangled in their content, helps to reduce the influence of these phenomena over meaningful activity; or that exploring ways to open up to, or to notice, the pull of pleasurable feelings helps to reduce their influence.

PIT

Psychodynamic Interpersonal Therapy (also called the Conversational Model of Therapy) was developed in the 1970s and draws on both psychodynamic and interpersonal principles, using jargon free language.

The therapy takes the form of an in-depth conversation between two people (client and therapist), in which the client’s difficulties are explored and hopefully resolved. In this sense, PIT sessions bear some resemblance to the kind of “heart to heart” conversation that we might have with a trusted confidante about a personal problem. PIT is more than this, however, because the therapist is trained to help focus the conversation on the most important issues for the client, and support them with any difficult feelings that this brings up.

PIT stems from the fact that people with psychological problems such as self-harm often report problems with managing their feelings, as well as difficulties in their relationships with other people. The PIT conversation therefore focuses on:

(a) the client’s emotional life including problematic feelings of which they are aware and difficulties they have perhaps pushed to the back of their minds (which is what the term “psychodynamic” refers to);

(b) the client’s relationships with other people (which is what the term “interpersonal” refers to); and

(c) how problems with managing feelings and relationships might link with difficult experiences in the client’s past, particularly with their parents or other important people.

The goal of the conversation is for the client to get a better understanding of their difficulties with feelings and relationships, so that they can manage their personal problems more effectively. The expectation is that this will lead to an improvement in their psychological symptoms as well. To do this, the therapist will often encourage the client to focus on and “stay with” difficult feelings that they experience during therapy sessions, so the feelings can be managed in the session, rather than talked about in an intellectual way.

Why PIT for NHS services managing repeat self-harm

PIT has been evaluated for the treatment of self-harm in a randomized controlled trial of 119 patients who were randomized to 4 sessions of PIT delivered by liaison nurse plus usual care versus treatment as usual alone (Guthrie et al, 2001). There was a reduction in reported self-harm in the six months post-treatment in the patients who received PIT in comparison with the usual treatment group. Approximately 50% of the patients who participated in the trial had a prior history of self-harm.

Following this study, an NHS treatment service, called the SAFE-team was established to deliver PIT to patients who had self –harmed (both repeaters and first episode patients). The service was based in Manchester and ran for over 15 years.

SAFE-PIT is the modified version of PIT that was employed by the service and is specifically tailored for people who SH. There is a focus on the most recent self-harm episode and an attempt to get the client to re-experience his/her feelings at the time of the self-harm behavior, to stay with those feelings and see what thoughts, images emerge. This process usually leads to a better understanding of the client’s difficulties and an improved ability to manage these difficulties. The process often involves some change in the clients’ relationships. A goodbye letter is given to the client at the end of the therapy to summarise the work and re-enforce positive change.